Washington County's Mastodon Relic

This artifact is a giant tooth of a Mammut, more commonly known, as a Mastodon on display in the Stevens Museum.In a large fossil display, in the children’s room exhibit, we have a unique item that occasionally catches some our visitor’s attention, without being pointed out. It generally sits on its top, as seen in the photograph below, and is not easily identified without reading the exhibit label. Over the years several people have spontaneously guessed it to be some type of petrified wood, or a chunk of a prehistoric tree. But neither of those are correct.

This artifact is a giant tooth of a Mammut, more commonly known, as a Mastodon on display in the Stevens Museum.In a large fossil display, in the children’s room exhibit, we have a unique item that occasionally catches some our visitor’s attention, without being pointed out. It generally sits on its top, as seen in the photograph below, and is not easily identified without reading the exhibit label. Over the years several people have spontaneously guessed it to be some type of petrified wood, or a chunk of a prehistoric tree. But neither of those are correct.

Along with the rest of the fossil collection, it is among the very oldest items we house at the Stevens Museum, dating back some 27 to 30 million years ago.

This article is indigenous to our county and our state. It was found in Section 35, of Brown Township, near the banks of the White River, by a local farmer, named, John McClintock (1844-1923), sometime during the late 1800s.

This artifact is a giant tooth of a Mammut, more commonly known, as a Mastodon. Mastodons are an extinct species of proboscideans (trunked mammals), and ancient relatives of today’s elephants. They stood between 8 and 10 feet tall, had a thick coat of hair, large floppy ears, and weighed between 4 and 6 tons, making them slightly smaller than modern African elephants.

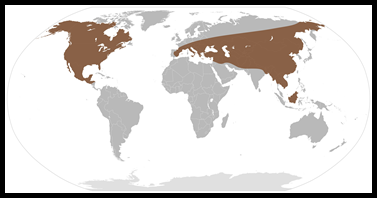

As you can see from the darker shaded areas, in the illustration below, mastodons were indigenous to a wide range around the center of the globe, and inhabited most all of North and Central America.

Mastodons inhabited North and Central America

Mastodons inhabited North and Central America

They were Hoosiers long before recorded history, enjoying Indiana’s swampy marshlands, which were perfectly suited for these forest dwellers, who made their homes in the woodlands near the bogs.

Sharing characteristics with the modern elephant, the females were smaller than the males. Likewise, the males had larger tusks, growing up to as much as 8 feet in length over their lifespan. Quite different from the elephant or the mammoth, however, were the teeth. The mastodons had conical or cusp-shaped teeth, whereas the elephant and mammoth have flat teeth.

Their teeth were well-suited for their mixed browsing and grazing diets, feeding on coniferous twigs, leaves, grasses, shrubbery, and low-lying herbaceous vegetation.

The species went extinct between 10,000 and 11,000 years ago, which scientists have attributed to both, overexploitation by Clovis hunters and climate change. Although recent discoveries indicate evidence of contact with tuberculosis.

The first remnant discovered of an American Mastodon was a 5 pound tooth, much like ours, found in a New York Hudson River Valley village, in the summer of 1705. The mystery animal the tooth belonged to became known as the “incognitum”.

This discovery came nearly a century before the discovery of dinosaur bones, so by the time a full mastodon skeleton was discovered in 1739, by French soldiers, at what became Big Bone Lick State Park, Kentucky, the creature had a grip on the popular imagination of the American colonies. According to Paul Semonin, author of "American Monster, a history of the Incognitum”; “Some primal force in the American spirit embraced it, as the nation’s first prehistoric monster.”

When similar teeth, tusks and bones started showing up in South Carolina and the Ohio River Valley, Americans began referring to the incognitum as a “mammoth”, after the woolly mammoths then being dug from the ice in Siberia. It would turn out, in fact, that North America had been home primarily to two different types of pachyderm—mammoths, like the ones discovered in South Dakota, and mastodons, like the ones found in the Hudson River Valley. But hardly anybody knew the difference.

After skeletal remains had been sent to Europe, European anatomists started to realize differences, by making side-by-side comparisons. Once again, the teeth of the mammoth and modern elephant are flat with a corrugated biting surface, where the incognitum had fierce-looking rows of large conical cusps.

That difference not only indicated that Siberian mammoths and the incognitum were separate species, but also led some anatomists to regard the latter as a flesh-eating monster. The British anatomist William Hunter wrote in 1768; “Though we may regret it as philosophers, as men we cannot but thank Heaven that its whole generation is probably extinct.”

Those teeth also eventually gave the incognitum a name. To the young French anatomist, Georges Cuvier, the conical cusps looked like breasts. So in 1806, he named the incognitum “mastodon,” from the Greek mastos (for “breast”) and odont (for “tooth”).

The discovery of such monstrous creatures raised troubling questions. Cuvier made the case that both mammoths and mastodons had vanished from the face of the earth; their bones were just too different from any known pachyderm. It was the first time the scientific world accepted the idea that any species had gone extinct—a challenge to the doctrine that species were a permanent, unchanging heritage from the Garden of Eden. The disappearance of such creatures also cast doubt on the idea that the earth was just 6,000 years old, as the Bible seemed to teach.

Mammoths and mastodons would shake the foundations of conventional thought. In place of the orderly old world, where each species had their proper place in a great chain of being, Cuvier was soon hypothesizing a chaotic past in which flood, ice and earthquake swept away “living organisms without number,” leaving behind only scattered bones and dust. That apocalyptic vision of the earth’s history would haunt the human imagination for much of the 19th century.

Caught up in the fervor, Thomas Jefferson, had convinced himself in the 1780s that the Mammoth creatures still lived in the vast American west. He wrote,”In the present interior of our continent there is surely space and range enough for elephants and lions.” Years later, when he was president, it was still on his mind and was an underlying reason he sent Lewis and Clark to explore the American West, to see if they could possibly locate a living mammoth. Jefferson once even had mastodon bones laid out on the floor of the East Room in the White House.

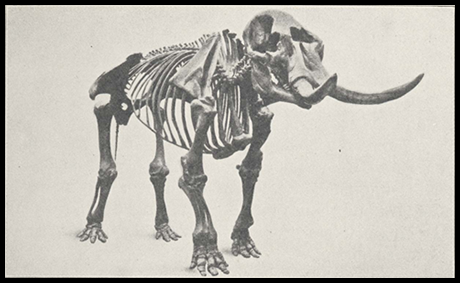

American Mammoth Skeleton

American Mammoth Skeleton

An 1801 reconstruction of a mastodon skeleton, in Philadelphia, was only the world’s second attempt with a fossil species. It was placed on display in America’s first national museum, opened in Philadelphia by Charles Willson Peale. Advertised as an American Mammoth, it became a national sensation, with word spreading until the masses of common people were now even more eager than the scientists, to view the great American wonder. Although this mammoth turned out to be a mastodon, the sheer bigness of the creature seemed to stir every heart and overnight the word “mammoth” gained spectacular currency in our cultural vernacular.

The mastodon bones are also attributed to starting a fossil craze across the globe that has led to an incredible leap in understanding natural history.

As it stands today, mastodon bones have been discovered in nearly all of Indiana’s 92 counties, so it’s not really that uncommon.

Several bones unearthed during a sewer excavation project on a farm in Seymour

Several bones unearthed during a sewer excavation project on a farm in Seymour

In 2013, there was considerable skepticism around the museum about our mastodon tooth being real or not. Again, many people thought it was some type of petrified wood. So one day, the following year, we were visited by long-time friend of the historical society, Dr. Richard Powell, who has his PhD in geology, was formerly a professor of geology at Indiana University, and has been a member of the Indiana Geological Society since 1957. While he was visiting in the library, I ran downstairs to retrieve our tooth to ask for his analysis and confirmation on what the item was.

When I reached the top of the stairs, on my return trip, Dr. Powell must have heard me coming, because after I cleared the top step and turned towards the library, he was looking at me and the object I was carrying. He immediately exclaimed, “Wow! You have a mastodon tooth!”

All doubt in the building was immediately erased from the good doctor’s 20 yard observation.

The tooth is among the favorite artifacts of our 4th grade school tours and shouldn’t be missed, so if you’re ever in for a tour, be sure to ask!

If you or anyone you know has discovered or ever discovers any skeletal remains of an American Mastodon in our county, we hope the parties involved will consider donating part or all of the artifact(s) to the John Hay Center, for the educational benefit of our future generations.